Death terrifies me, yet I read cemeteries like books.

Each graveyard is like a library. Each stone, a chapter in its collection. My imagination resurrects their dead, gives them flesh and features. A voice. I am no vampire, yet their stories nourish my soul.

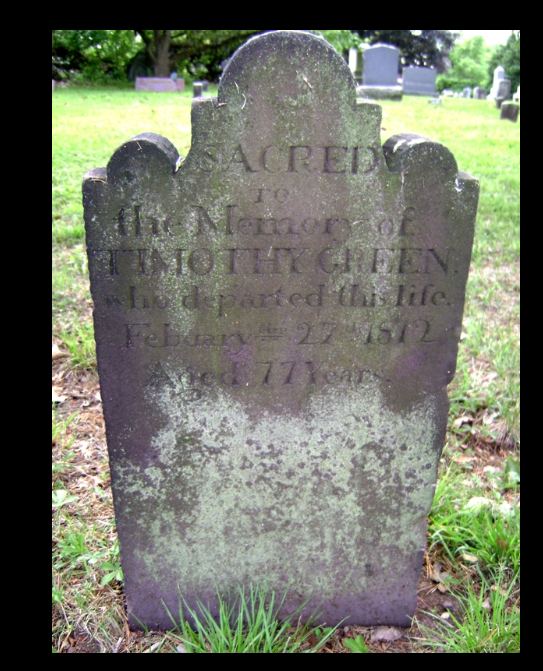

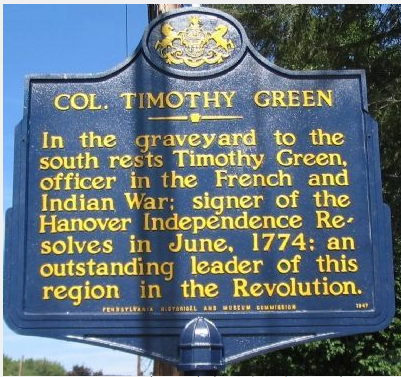

My fascination began in 1976, with the cemetery around the corner from my house in Dauphin, Pennsylvania. Sometimes nine-year-old me walked there, sometimes I rode my green banana seat bike, cutting through the poplars lining our backyard through the neighbors’ lawns to Charles then Floral Lane, all the way to where pavement became a dirt road slicing the old growth woods within which a drug-dealing, child-eating murderer resided.

That last bit we children made up from scraps of overheard teenage gossip and the eerie lights and noises rising from the forest’s Halloween enchantments. I never trick-or-treated down that road.

Strangely, however, its cemetery neighbor never frightened me.

Maybe because I never visited it at night (I’m not THAT brave). Maybe because I didn’t really understand what dead meant. Everyone I knew was alive. Literally, of course. Corporeally. But also metaphorically, in the factual and fictionalized stories that were told about them. My imagination conjured characters from their pages, so of course they were as ‘real’ as people populating my physical world. In the months approaching America’s Bicentennial, I’d read Johnny Tremain several times, and I’d sung Yankee Doodle in Middle Paxton’s school pageant, flag waving, while costumed in my red, white, and blue Little House bonnet. Imagine my delight then, to discover not one but over a dozen tombstones commemorating local Revolutionary War heroes.

Since then, of course, I’ve lost too many colleagues and classmates, too many family members and friends. Cemeteries resonate much differently now, yet still I wander their pathways. Searching, reading. Trying to understand.

Recently, I spent solitary hours of a New England road trip doing just that in Salem’s Charter Street Cemetery and its adjacent Witch Trials Memorial. Summer had come late to Massachusetts—90+ degrees in September—and although we had traveled New England years ago, this was my husband’s and my first visit to Salem.

Day one, we walked miles exploring the village’s infamous history. Day two, we logged several more miles exploring its western shore, including the Turner-Ingersoll Mansion, more famously known as the setting of Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The House of the Seven Gables.

While the mansion stands where it was constructed in 1668, the property’s other five buildings were relocated from throughout Salem as the mansion transitioned from a private residence to a national historic district. On our morning tour, our guide had explained that in the early 1800s, Nathaniel Hawthorne would frequently visit his much older cousin Susanna Ingersoll, who regaled him with stories of their shared history, as well as her home’s architectural metamorphosis. In Hawthorne’s lifetime, the house lacked its now famous gables, as they had been removed by a previous owner who loathed its gothic silhouette.

Since then, the mansion has not only been restored, it’s been adapted. Caroline Emmerton, who purchased the residence in 1908 intending, in part, to preserve its legacy by converting it to a museum, recognized that much of its attraction lay in its connection to Hawthorne’s novel. Thus, the additions of Hepzibah’s penny store and the secret stairs hidden behind the dining room hearth, two features the original home never contained. Like a weaver at his loom, our guide alternately entwined and unraveled the threads of fact and fiction’s interconnected past, ultimately creating a tapestry that illuminated Hawthorne the writer and man. Haunted by an unrepentant ancestor’s role as judge in Salem’s bloody witch trials, his life and fiction strived to answer questions his cousin’s recollections could not:

Must we repeat familial and historical mistakes, or can we learn from them and act to improve our futures?

Such questions haunted me that day as well, so I bought a copy of Hawthorne’s novel and headed to the Witch Trials Memorial, while my husband returned to the hotel to literally chill.

As I approached the memorial’s granite boundary, a weak breeze rustled the surrounding leafy canopies but provided no relief. A forecasted cold front had yet to manifest, and despite thin, gray clouds, the heat had become nearly unbearable, the humidity steaming like a stove pot. Locust trees within its grassy middle offered welcome shade, but fewer than a dozen visitors had crossed the memorial’s stony threshold to where they beckoned. Most who did were grouped in the far left corner listening to a tour guide and village native share his aversion to his hometown’s touristy commercialism. I think it’s important to take a few minutes to recall that people died here, he told them. Innocent people were murdered.

Reading the threshold’s interrupted benediction, I nodded.

Twenty, to be exact.

Nineteen of them hanged, one of them pressed to death by stones. Five more innocents died in prison awaiting trial. Rebecca Nurse, at whose stone bench I stood for several minutes, had been initially acquitted by her jury. However, confronted by the jeers and contempt of spectators attending her June 1692 trial, they returned to their deliberations and this time returned a guilty verdict. Two weeks later, the 71-year-old grandmother and mother of eight was executed, hanged on what became known as Gallows Hill. In October, Massachusetts Bay Colony Governor William Phips ordered the trials’ cessation and the release of approximately 150 accused still imprisoned in Salem’s inhumane dungeon jails.

His wife, you see, had been recently accused of witchcraft.

Exiting the memorial, I crossed to the cemetery’s entrance, where an attendant offered paper maps and answers to any questions my contemplation of its grounds afforded. I thanked him, then circled right, avoiding the flow of visitors gravitating toward the clockwise path. Several yards ahead, a familiar black and white checked blouse meandered among a cluster of tilted tombstones and what appeared to be a mausoleum. It was the woman from the morning’s mansion tour. She’d seemed as intrigued as I by the intersection between fiction and historical record and likewise had peppered our guide with questions, eagerly darting ahead of me through the hidden entrance to the narrow attic stairs. This would be my room if I lived here, I told her as we gazed through a gabled window to the harbor and grounds below. Now here she was again, wandering Salem’s graveyard.

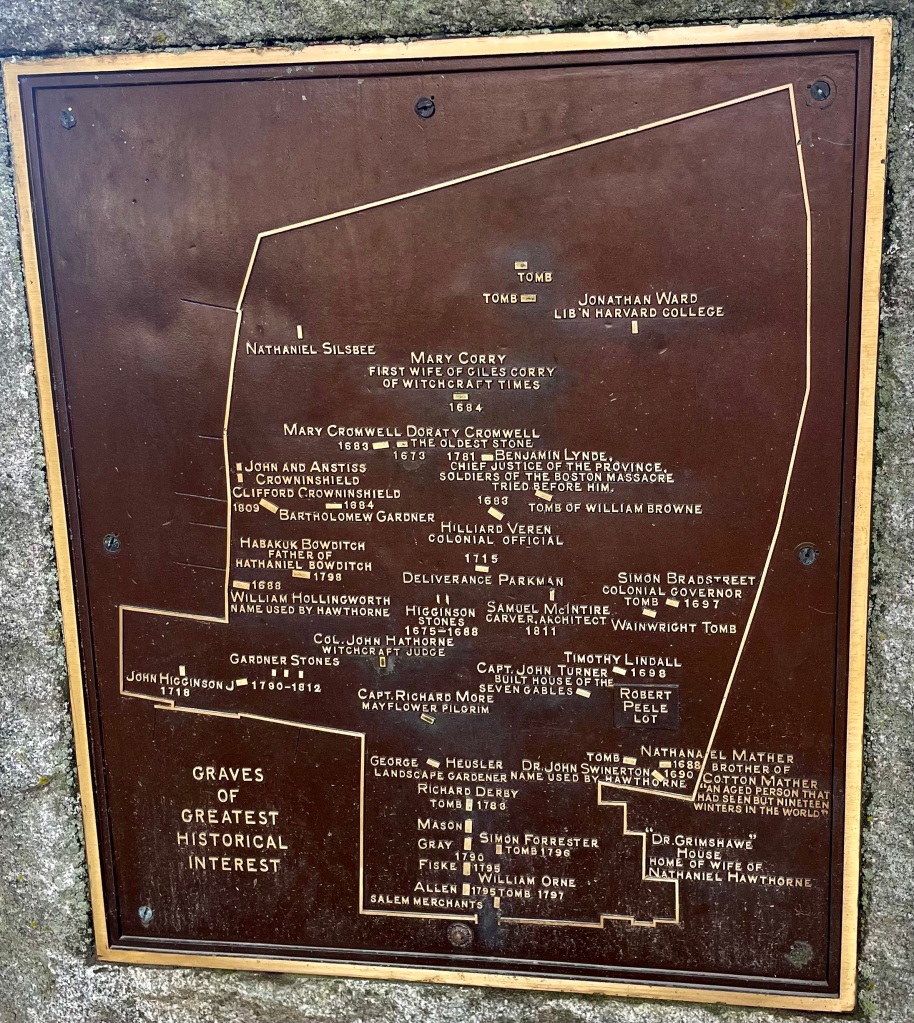

Established in 1637, the now National Historic Landmark was reopened in 2021 following a years-long restoration of and improvements to its grounds and several tombstones. Strict instructions for ensuring its continued preservation greet contemporary visitors, including Stick to the Path and Look, but Do Not Touch. A deceptively easy admonition, because unlike more modern graveyards–uniform tombstones and gridded plots–Charter Street’s hodgepodge markers are irregularly spaced, irregularly oriented, some of their faces turned away from their neighbors’ and mine as if engaged in cosmic hide-n-seek. Likewise, the ravages of time and weather have smudged and frequently erased the carvings on softer, older headstones, rendering their inscriptions impossible to discern.

Nonetheless, I read what I could, discovering such notables as Mayflower Pilgrim Thomas More and witch trials judge Col. John Hathorne, author Nathaniel’s great-great grandfather. However, like most graveyards, most of those buried within its 1.47 acres were ordinary people like you and like me. Someone’s child, someone’s spouse, living and working until one day they didn’t, leaving on this side of the soil those of us who somehow must go on.

Until, of course, death calls us to join them.

I settled on a bench, prolonging my necessary departure. From its perspective, I could see the entire cemetery and the memorial beyond. Few visitors remained within. The sky had darkened, its earlier smooth gray slate replaced by herniated purples, its breeze no longer stultifying but cold and pimpling the flesh of my forearms. Even the trees seemed to shiver, anticipating rain. I wondered how long they’d stood witness, how much longer they’d remain upright.

Standing, I crossed to the attendant. I had questions, and he promised to give me answers.

A lifetime spent reading cemeteries has taught me that, like memorials, they reveal at least as much about their living as their dead.

Even omissions tell a story. Consider, as I did, a child’s grave marked only with their given name, their birth and death years identical, their parents’ stones like arms on either side.

I know you can read that story. I know you know how absence feels. Omissions form the foundation upon which truth must rest.

As I’d suspected, the attendant told me none of the murdered twenty are buried within Charter Street. In fact, none of the murdered were even Salem residents but lived in outlying villages and farms. Most likely their bodies were retrieved by family who, perhaps obscured by nightfall, buried them in unmarked graves somewhere on their homesteads rather than risk further retribution.

We’ll probably never know.

Nor will we ever know the identities of those who lie beneath the graveyard’s blank stone markers. While some of them are documented in early 1900s photographs, the attendant told me, many are not. Those inscriptions are lost to time and memory, as are the hopes and dreams–and failings–of those whom stone itself failed to immortalize.

Perhaps you wonder, Why does that even matter? What point is there in wondering about the so-long-dead and gone?

I say, Because their histories reflect on our present.

Because someday, our present will be tomorrow’s history, our tombstones a kind of portal through which our legacies travel.

Because legacies are like themes–the meanings inherent in both stories and in life– and are created not only by the visible but by the buried. By the friction between what should be there yet isn’t, and the understanding that arises through our quests to reunite them, allowing us to see both our individual significance in humanity’s story and our opportunities to impact its arc.

The dilemma, of course, lies in how we choose to act on those opportunities.

You see, it’s not the death of our bodies that terrifies me. I know none of us are getting out of here alive.

I’m terrified by the death of our souls. Of whatever you want to call the universal light within our human consciousness that prompts us to be our better selves. So much of what I see in our world celebrates our baser tendencies–Ignorance. Greed. Self-interest. They couple with hatred, birthing evil, and I wonder, In such an ugly world, why bother striving, why bother caring when humanity seems hellbent on its own destruction?

Reading cemeteries helps me keep my better self alive.

They tell me stories not only of endings, but beginnings. Stories of good versus evil. Hope versus despair. They remind me that I am not alone. That my actions have power. Influence. Impact. Even inaction alters history. Mine. Yours. Ours. Each choice to confront or collaborate with evil inextricably binds us in ways far beyond our immediate capacity to know and understand.

Barely twenty years after her death, Rebecca Nurse was the first of those convicted to be formally exonerated. Three hundred years later, the Witch Trials Memorial was dedicated by Holocaust survivor and Nobel Laureate Elie Weisel. And just last year, August 2022, Massachusetts formally exonerated Elizabeth Johnson Jr., the last of Salem’s falsely condemned, following the efforts of eighth-grade civics teacher Carrie LaPierre and her students.

Col. Hathorne must be rolling in his grave to be thus thwarted.

As I finished speaking with the Charter Street attendant, our phones shrilled with a National Weather Service alert. The storm had intensified, its wind and lightning potentially life-threatening, and anyone in its path was urged to take cover. I power walked the mile or so to our hotel and arrived just as the skies burst. However, despite the forecast’s promised fury, by the time I exited the elevator at the fourth floor, the storm had all but passed, leaving no more damage than a few leaves skittering among the sidewalk puddles. Husband and I showered then changed for dinner, walking hand in hand to an Italian restaurant we’d seen earlier, a few blocks away.

How’s your book, he asked me afterwards, college halftime catastrophizing on the flatscreen.

Twilight winked through our floor to ceiling window walls and illuminated foot traffic crossing Artists’ Row to Essex Street’s pedestrian mall. Sinking into a fat orange armchair, I opened the hardback on my lap.

I’ll let you know, I said, turning to the preface.

I wanted to binge, but I savored, reading through chapter one that night, then bookmarking my stops as we continued our trip through Maine and New Hampshire. Through Vermont and back to Pennsylvania, where I finished a few nights after our return home.

There are some books that speak to the child you were. Some that speak to the adult you hope to be.

Gables, for me, is the latter.

Not merely because of the story within its pages–Its prose can be convoluted, its pacing tortuously slow.

Rather, because the fictional story within its pages continues the factual story without–The House of the Seven Gables isn’t only about Maule’s execution and Hepzibah, about whether Phoebe will wither among the mansion’s shadows or dispel them. It’s about Hawthorne asking and answering questions much like those I asked myself while reading the Charter Street Cemetery. It’s about Hawthorne sharing his conclusions with the universe, about his trying to affect its trajectory for the better.

Not perfectly, perhaps. Not definitively. The novel’s perspective, like its author’s, can seem dated to contemporary audiences, and Hawthorne the man was likewise an imperfect creature.

Yet authorial intentionality notwithstanding, he could have written a different book. He could have written a different ending. He didn’t, however. He wrote this book with this ending and thereby changed our conversations–our records–about one of the ugliest chapters in American history. History isn’t destiny, his novel suggests. We can do better, and we must.

The woman in the checked shirt seemed to agree.

Our paths had crossed again, beyond the Peele family lot and Governor Simon Bradstreet’s tomb, and we chatted a bit more. Like me, she had temporarily abandoned her traveling companion to reckon with the village’s ghosts and to some extent, her own.

I never learned her name. I never gave her mine.

Yet, we both smiled to have discovered a kindred spirit so unexpectedly, so very far from home.

*****

I usually post the first Saturday of each month.

NEXT UP: The first in an occasional series on BOOKS THAT MATTER, including conversations with reader friends about the books they cannot live without.

And later in 2024: HARRY POTTER AND THE CULTURE OF ERASURE

Thanks for reading 🙂

Discover more from My Name was Supposed to be Elizabeth Ann

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.

I’ve walked through that cemetery in Salem. So much of the town speaks to me. Thanks for sharing your experience. It takes me back.

LikeLiked by 1 person