It’s a puzzle, ain’t it? How sometimes life gives you all the pieces but their edges are rough and the colors are blurry and it ain’t till you step a ways back and rearrange that you see the patterns. You know? You asked what brought me here and I’ll tell you, but first I got to tell you something else. Since Pa died, I barely spoke, but after the ruckus in church a few weeks back my words is like a fountain. You don’t mind, Ma’am, do you? We got time.

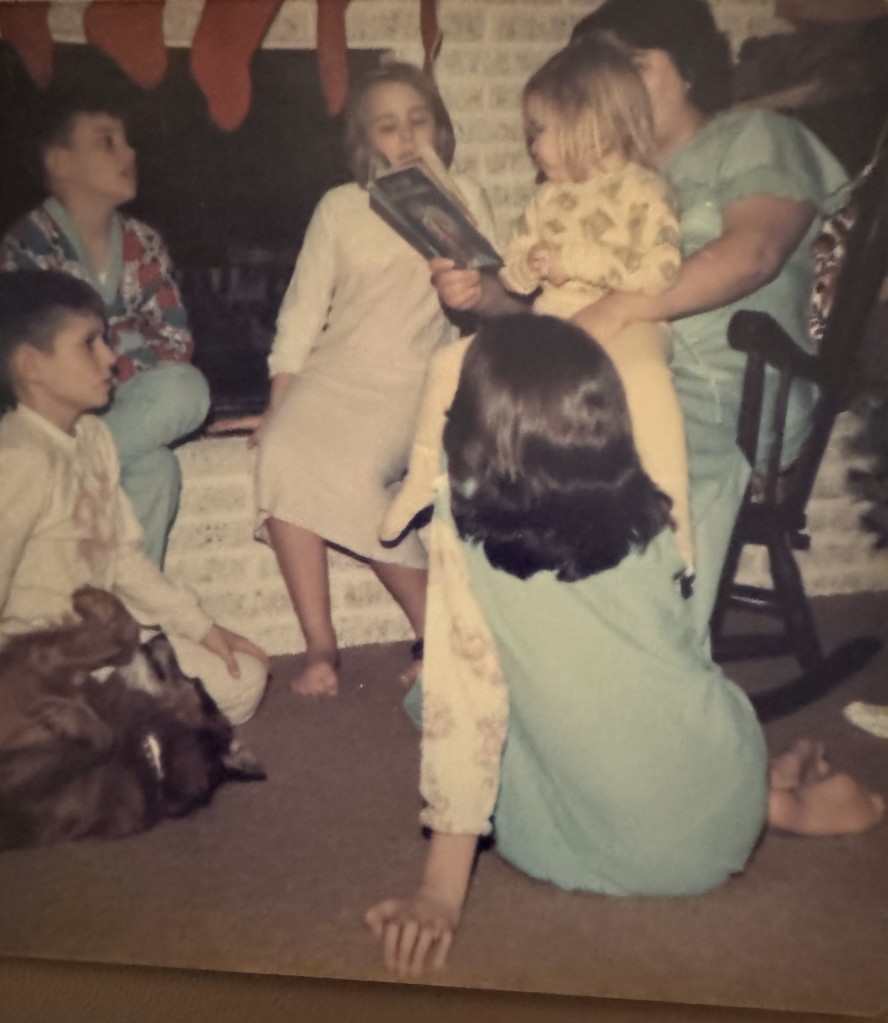

Anyhow, Ma and me live a ways out of town, near where the river bends like an elbow. You can see it from the train bridge, over there. Our house’s the one made of two squares, a big one and a little one, plus a shed out back where Pa kept things like hoes and threshing rakes for Ma’s garden. The big square is where we done our eating and sleeping, Pa and Ma in a nook off the kitchen and us four children in the loft. Evenings, Pa’d tell stories and Ma’d rock by the fire knitting or sewing up the holes in Brother’s shirt. Sometimes I sat in Pa’s lap, sometimes on the floor. That was my spot, Ma tells me. Near Pa.

It’s a puzzle, ain’t it? How sometimes life gives you all the pieces but their edges are rough and the colors are blurry and it ain’t till you step a ways back and rearrange that you see the patterns.

The time I’m needing to tell you was one of those days can’t make up its mind to be spring or winter. Ice melting and muddy, but the sun shining like a promise ring. I remember Ma and Pa both was in a tizzy, though I did not know why. I’s fourteen now. Then I’s only six. Anyhow, we hadn’t a real preacher for longer than I’d been alive, the last one an itinerant came through for the christenings and deaths. Sometimes weddings. So Pa and the other men would do the preaching, telling stories that I thought were Pa’s stories but turns out belonged to Jesus and his own pa, which a course I thought was the same thing. That day we was supposed to get a new preacher and someone, Ma can’t remember, decided Pa should do the welcoming.

Me, I remember the kittens. Kitty had them in the shed in a little soft hole in the corner where Pa told me I could look but not touch, at least until they was weaned or their eyes opened. Which for me was the same thing. He told me I could have one when they’s grown, so I picked the runty one cause she’s little like me but I didn’t tell no one. I’d study them for hours and tell Pa’s stories to help them grow like Pa’s stories helped me. That day, four a them had their eyes open but my runty one didn’t. I knew I shouldn’t touch but I did cause the littlest one wasn’t moving and I wanted to get it to move. It was dead, which I knew but didn’t want to know. I remember running for Pa. He’d told us bout Jesus resurrecting from the dead and I thought Pa could bring Kitty’s runty kitten back alive like he done Jesus. I remember the mud squishing my toes and slowing me down like fingers grabbing at my ankles. I didn’t think I’d ever find Pa, but when I circled the house, I heard Pa and Ma telling my sisters and Joe our brother to settle, and then another voice I didn’t reckon. Both low and loud at the same time, like how thunder starts quiet then blows like a wave through the clouds. I thought, or maybe heard, I don’t remember exactly, that somehow Pa had knew and asked Jesus direct about Kitty’s kitten.

Well, I burst into the house babbling like Ma tells me I used to do and I seen a man who wasn’t Jesus at all but a man in black with a frown like Pa’s scythe and he’s helping himself to the last of Ma’s turnips. Children should be seen, not heard, he says, nodding at Ma to scoop another turnip on his plate. The only plate on the table.

I threw a tizzy, Ma says. I’s so mad cause Pa always told me I should ask when I need something, and here I was asking and he ain’t doing nothing but minding some stranger without manners enough to share. I must of said as much cause Pa said I’s being disrespectful and to wait outside till I find my own manners. I should be ashamed, he said, scampering all over Ma’s clean floor with my muddy feet and interrupting Preacher. Mind you, I did not know Preacher was Preacher until Pa’s service and then it’s too late to hush.

The day after Preacher came, Pa died and I stopped talking to most everybody cept Ma and sometimes Schoolteacher. Miss Sophie’s the one what taught me to write my stories if I couldn’t see fit to talk them. She came year before last, after the measles took the last one. That ain’t how Pa died, though. Him and the other Pas was plowing the big farm in the hollow over there when one a the draft horses got spooked. No one seen why, least that’s what they told Ma who’s left with four children to raise, me being the youngest. Joe quit school and hired himself out in Pa’s place. Our sisters wasn’t much for schooling, not like me a tall. They stayed long enough to cipher and tally bills at the mercantile. First for us and Ma, then for they own husbands and children. Janie has two and Sarah has one, a little girl with green eyes like mine. I love her especially. She is three and fierce like a lion. Which I ain’t never seen but imagine from the books Miss Sophie let me borrow cause I take care of them and bring them back to school on Mondays and after planting and harvest. Preacher has the running of the school in between harvesting souls. The wheat from the chaff, he says, though he can’t tell a spade from a shovel if you catch my meaning. Miss chuckled when I told her on my slate. Then she told me to tell her out loud and I did. And then I told her about Pa.

Last month, I heard Preacher and Miss talking in the schoolhouse while I’s outside reading and the other children was playing marbles or some such so’s Preacher could have his word. I’d been feeling poorly, like I’d swallowed a bag of rocks, cause Miss said she’d done taught me everything she could and it was time for me to graduate. She’s planning a whole ceremony, she said. A commencement. I never heard that word before so I looked it up in the fat dictionary Miss keeps longside her desk. She’d got it wrong, I read. I wasn’t beginning something, I’s ending. There ain’t no secondary school anywhere near here and besides, Ma said it’s time I got a job like Joe and our sisters when they’s my age. I even wrote another story about it, trying to keep my innards steady, but every time I thought about leaving school, I swallowed another rock.

Anyhow, my breath got hitchy when I heard my name cause I thought I was in trouble even though I hadn’t done anything wrong that I could remember. Mind you, I was not eavesdropping. Preacher is loud and forgets I can hear just fine. Miss’s voice was happy like sugar and she’s telling Preacher I’s the smartest she ever seen, like a dry riverbed drinking up the rain. She told Preacher she put some a my stories in the post and some school up north wants me to study there, the same school Miss told me she’d gone to. Can you believe it? Tuition included, plus a place to stay. I’d just need travel money and a few extras, which I could get working in the school kitchen once I got there, and Miss asked a course could the church help?

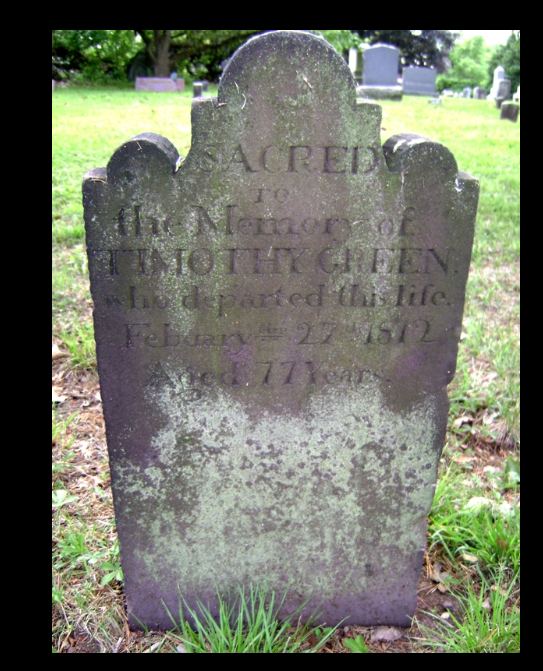

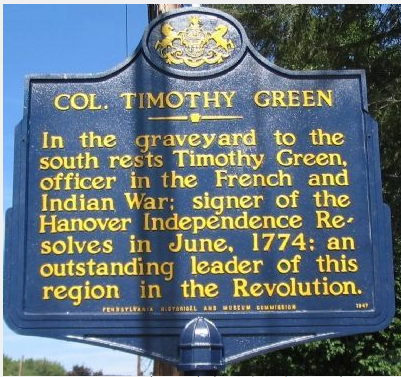

Preacher, he just laughed. Mind you, there’s all kinds a laughs and you can read them like you read a book. Ever notice? Least I can, and Preacher’s laugh was like someone showed him a porcupine and told him he could magic it to a squirrel. He said there had to be some mistake, surely one of the boys’d be a better candidate than a half-wit girl and he’d see to fix it. Well, Miss’s voice went from sugar to fire, like each word’s a match, till Preacher said something about contracts and options and how St. Paul certainly had it figured when he told Timothy’s womenfolk to hush. After all, if it ain’t been for Eve talking to that snake we’d all still be in Paradise stead a this Podunk town. Miss got real hushed then. I waited till Preacher left and I seen Miss sitting at her desk with her head in her hands and her face grim like…Well, I don’t rightly know. But she straightened right up when she saw me, she knew I heard. We’ll figure something she said, I shouldn’t worry.

But a course I worried. All Miss done was try to help me, I didn’t mean for Preacher to trouble her. It was like Kitty’s kittens when I’s little. After I interrupted Preacher’s supper, Pa and Ma shared a frown and Pa told me to get along outside, he’d be along after a bit. But the words in my throat was rushing and I did not listen. I hollered something ugly and ran to the shed for Pa’s shovel and some rocks cause I remembered the part about the angels rolling the rock away. Pa’s stories was all jumbled in my thinking, and a course I’s too little to figure the shovel. I cut up my feet something fierce and started wailing at the gush a blood. Pa and Ma both came running, Preacher a ways behind with his napkin tucked in his collar like some flag. Next day, Pa tucked one a the boss’ spare kitties in his pocket meaning to walk home noon hour to give it to me, ‘cept it got loose and spooked the horse.

I ain’t supposed to know that but I do. I told you Preacher talks too loud.

Anyhow, try as we might, Miss and me couldn’t figure a way to raise the money. Ma had a little extra but it weren’t near enough, and Miss needs her extra for her own ma and pa back home. Miss even wrote to the school but they’s sorry they couldn’t do anything else but hold my spot awhile if need be. You’re right Ma’am, times is tough everywhere. Ma said it’s for the best but her eyes was contradicting her mouth. All this is yammering in my head in church last month when Preacher’s preaching bout prayer. He’s saying how God is good to His children like our papas is good to us and that got me thinking about my own Pa. I closed my eyes so’s I could remember better. I’s thinking he could a figured a way, Ma said Pa could fix most anything. I missed him a course, but not as hurtful as it used to be. Mostly I missed how he used to explain things sweet and easy so’s I could understand. Pa’s why I loved school so much, least after Miss came, cause Miss learned us with stories like he done. Meanwhile, Preacher’s preaching about asking and receiving and I recollected how Pa used to tell me all I had to do was ask and Pa’d see what he could do. I also couldn’t sit on my behind, Pa said. I had to do some a the work. He said it’s kind a like when you lose something. The asking kind a quiets the yammering that keeps you from seeing what needs seeing. The rest is like walking through an unlocked door.

But as I’m thinking this, I’m hearing Preacher and he’s telling it all wrong. Like he’s the only one can see who’s asking proper. That got me so mad, let me tell you. Ain’t no one more proper than Pa and Miss, and Preacher got no right saying otherwise. I scrabbled across Ma for a prayer book and turned to where Preacher’s railing and there it is. Matthew’s story, same as my own Pa’s name. Ask and ye shall receive, seek and ye shall find, knock and it shall be opened to you. Can’t be anymore clear than that. Anyhow, I don’t even know what I’s thinking. I just stand up and tell Preacher he got it all wrong. He’s gone around telling me and Miss and near half the congregation we ought a hush when it says right there we gotta open up our mouths what God gave us. Ain’t no way He’d of ever wanted us to hush. I said I tried hushing after Pa died, figuring keeping quiet’d fix the mess I made killing my Pa in the first place, even though I ain’t mean to cause I’s little. I told everybody I ain’t no half-wit like Preacher says, I’s smart and so’s Miss. Miss is the one what figured out my mess when nobody else seen it. She told me Pa wouldn’t of wanted me to feel bad about his accident. She told me Pa was a teacher like Preacher ought a be, telling stories and showing me the right a things. I told everybody about Miss’ school and how I’s gone write and tell them to hold my spot, even if I got to work till next year for the money. Everybody’s looking between me and Preacher then me again, till one of the pas Pa used to work with marches up to the altar and grabs the collection basket. Everybody starts filling it with pennies and nickels, even a silver dollar, and one a the Elders says they needs a meeting bout Preacher’s contract. Ma, she starts crying and hugging me and Miss. Miss just smiles big as a rainbow. Told you, she tells Preacher. She’s the smartest I have ever seen.

A course I cried too and then I hollered a thank you so loud it woke the babies, but the mamas, they just let em cry.

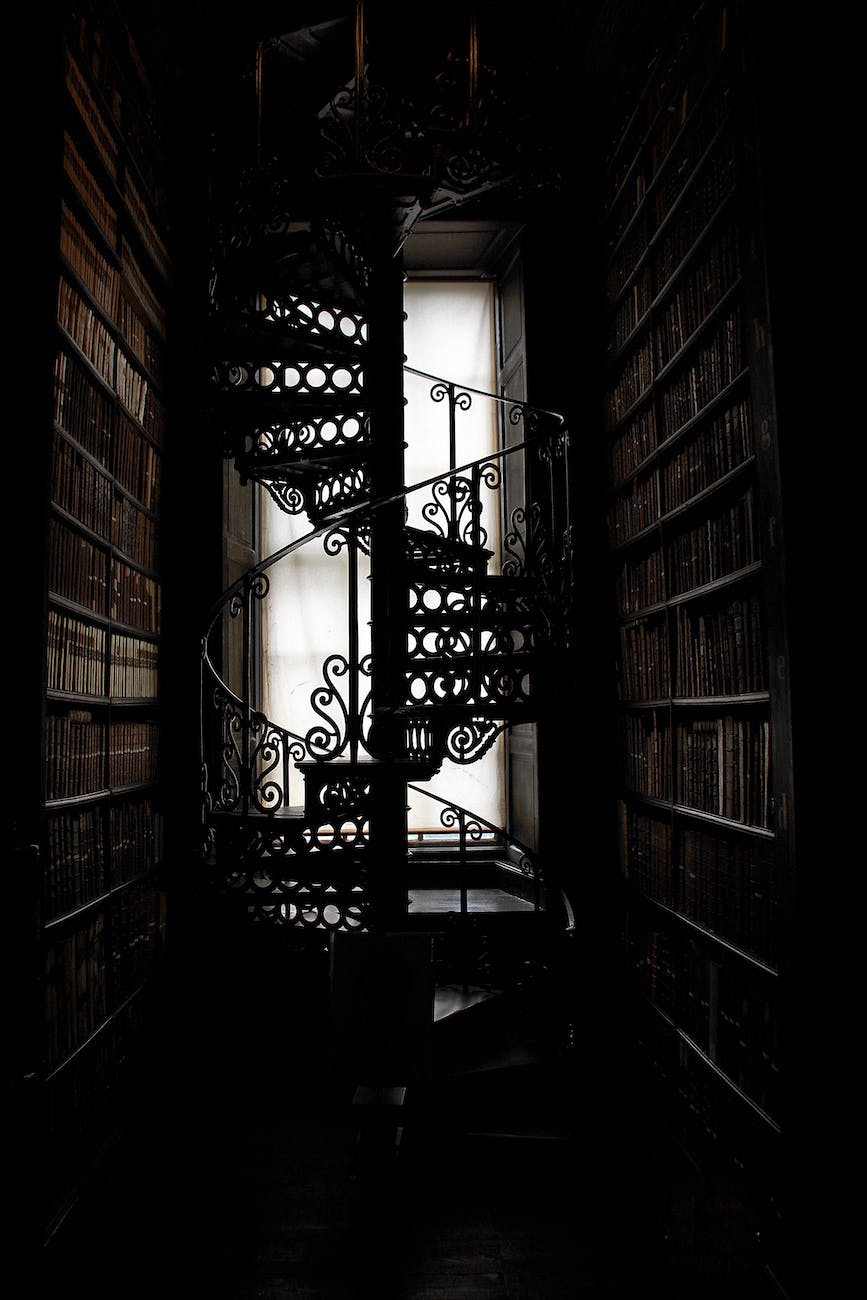

Which is why I’m heading on the train like you, Ma’am, I got a ticket right here gone take me to my new school. Everybody chipped in, even Preacher. Though I could of swore he done it with a bellyful a rocks. Anyhow, Miss says if I study real hard and practice my speaking, soon enough I’ll be even smarter. I will a course, cause telling you this I figured the last piece a my puzzle. I’m gone write me a schoolful a books, bigger even than the one Miss says is at my new school, and I ain’t never gone hush again.

*****

ASK AND YE SHALL RECEIVE originally appeared in Stories That Need to be Told (TulipTree Publishing / Jennifer Top, ed.)

*****

Coming next Saturday in Book Talk…. The Road Not Taken or, How My Life Plan Got Derailed in Seventh Grade